Using a desktop/laptop? Want to see more content? Click:

Desktop Version

Desktop Version

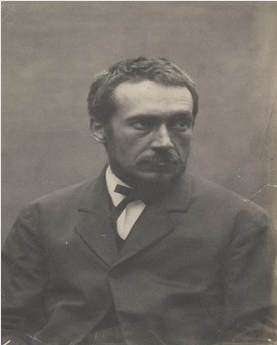

The Naked Truth about Thomas Eakins

By Greg Freeman, Published January 6, 2020Born in Philadelphia, Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (1844-1916) would distinguish himself as a realist painter, sculptor, photographer and fine arts teacher, securing his place among the most important and celebrated artists in American history. His portraiture, in some ways, captured the soul of Philadelphia. His images of athletes in motion, inspired by the work of Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), as well as his nudes, both paintings and photographs, were groundbreaking explorations of human anatomy. In typical Eakins fashion, the nudes testified to the beauty of the human form, both in pose and action, and challenged late nineteenth-century social norms. Brilliant and highly skilled as he might have been, Eakins' work was not fully appreciated until after his death. Due to scandal that erupted over his personal behavior and some of his more controversial decisions as a fine arts educator, Eakins' career has been revisited and reexamined in recent years, particularly in the wake of institutional sex abuse exposés and the enlightenment of the #MeToo era. Many questions regarding Eakins' sexuality, his actions and his intentions remain unanswered. On the other hand, some observers might even indicate that his body of work, for better or worse, leaves little to the imagination, but is that truly the case?

Eakins Goes to Paris

Athletic and artistically inclined, and effiminate with a woman-like voice by some accounts, Thomas Eakins, the son of calligrapher, Benjamin Eakins, displayed a propensity for mechanical drawing in high school where he, incidentally, met future landscape painter and lifelong friend, Charles Lewis Fussell (1840-1909). Following high school, the two would study at Philadelphia's Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, beginning in 1861. Additionally, Eakins enrolled in anatomy classes at Jefferson Medical College where he furthered his understanding of the human body by attending lectures and participating in the dissection of cadavers. While a career in the medical field merited his consideration for a season, he ultimately stayed true to his artistic calling.

From 1866 to 1870, Eakins studied art in Europe, first with academist painter and sculptor Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, then with realist painter Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), before moving on to Spain where he found the work of the important Spanish Golden Age figure, Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660), particularly refreshing.

Eakins' time in Paris had opened his eyes to a Bohemian milieu in which great artists, writers and cantankerous expatriates would soon flourish during a period known as La Belle Époque. He was hardly impressed with the works of Édouard Monet (1832-1883) or Edgar Degas (1834-1917), whose new style of painting would not be called impressionism until 1874. Eakins would have surely encountered brazen homosexuality among the liberally-minded Parisians. For those who contend that he was a closeted homosexual or, at the very least, bisexual, there is some speculation regarding his sexual explorations during this time period. As an art student, he had viewed the female form from the vantage point of devoted artist, but expressed a fervent desire to work with the male form as explained in a letter (although hardly a confession of homosexual longing) to his father:

From 1866 to 1870, Eakins studied art in Europe, first with academist painter and sculptor Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, then with realist painter Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), before moving on to Spain where he found the work of the important Spanish Golden Age figure, Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660), particularly refreshing.

Eakins' time in Paris had opened his eyes to a Bohemian milieu in which great artists, writers and cantankerous expatriates would soon flourish during a period known as La Belle Époque. He was hardly impressed with the works of Édouard Monet (1832-1883) or Edgar Degas (1834-1917), whose new style of painting would not be called impressionism until 1874. Eakins would have surely encountered brazen homosexuality among the liberally-minded Parisians. For those who contend that he was a closeted homosexual or, at the very least, bisexual, there is some speculation regarding his sexual explorations during this time period. As an art student, he had viewed the female form from the vantage point of devoted artist, but expressed a fervent desire to work with the male form as explained in a letter (although hardly a confession of homosexual longing) to his father:

She is the most beautiful thing there is in the world except a naked man, but I never yet saw a study of one exhibited...(Homer, 1992)

Prior to departing for Paris in 1866, Eakins had been romantically involved with budding painter and engraver Emily Sartain (1841-1927), the sister to his good friend, William Sartain (1843-1924), a future orientalist and portraitist. (The Sartain siblings were from a great artistic dynasty.) While the years of separation led to the demise of his relationship with Emily, Eakins was joined by William in March 1869. The two shared Eakins' studio space and studied at the atelier of Bonnat. Soon thereafter, Eakins felt confident that he had sufficiently learned the fundamentals of realism and was ready to seriously embark on his artistic career back home in the USA.

Prior to departing for Paris in 1866, Eakins had been romantically involved with budding painter and engraver Emily Sartain (1841-1927), the sister to his good friend, William Sartain (1843-1924), a future orientalist and portraitist. (The Sartain siblings were from a great artistic dynasty.) While the years of separation led to the demise of his relationship with Emily, Eakins was joined by William in March 1869. The two shared Eakins' studio space and studied at the atelier of Bonnat. Soon thereafter, Eakins felt confident that he had sufficiently learned the fundamentals of realism and was ready to seriously embark on his artistic career back home in the USA.

When Eakins arrived in Philadelphia on July 4, 1870, his career soon began in earnest. Eakins' father would eventually provide his son with a fourth-floor studio addition to the Eakins family residence at 1729 Mount Vernon Street.

Stunning Revelations and Accusations

Thomas Eakins' early works included various portraits, rowing scenes, including Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (1871), and the monumental painting, The Gross Clinic (1875), a shockingly realistic portrayal of the famous surgeon, Dr. Samuel D. Gross (1805-1884), at work in the surgical theater. One of the greatest American paintings of the nineteenth century, The Gross Clinic sold for $68 million in 2006.

In 1879, Eakins joined the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, as an assistant to Christian Schuessele (1824-1879), who was failing in health and serving as professor in name only. Eakins basically revamped the curriculum in Schuessele's absence and worked without compensation while Schuessele continued to receive much-needed income from the school. Following Schuessele's death, Eakins was named Professor of Drawing and Painting in August 1879 and became the director of the Academy in 1882. Right away, he disregarded some long-standing rules, including those prohibiting the use of students as nude models. In an era in which women wore full-skirted dresses, it must have seemed outrageous that a male model might be asked to pose in women's life classes. Nonetheless, Eakins tredged on, having students pose for his own works, posing both male and female students for his Naked Series of photographs and even exposing himself to a female student under the auspices of showing pelvic movment. Eakins, no doubt, crossed any number of lines, but his openness to working with nudes proved trendsetting. In a piece for Antiques & Fine Art Magazine, Dr. Cynthia Roznoy wrote, "Eakins' efforts shifted the whole of art teaching in America; by the turn-of-the-century life classes were sanctioned and the male nude emerged from his classical guise to be seen as a contemporary subject" (2012, 152-157).

At the age of forty, Eakins married twenty-five-year-old Susan Hannah Macdowell (1851-1938), and their marriage would conspicuously remain a childless one. The two had met at the Hazeltine Gallery in 1876 during an exhibition of The Gross Clinic. Macdowell had been intrigued by the controversial painting and went on to study with Eakins at the Academy where she became a proponent of including women in life-drawing classes in which the models were nude. In 1886, Eakins was forced to resign from the Academy after he removed the loincloth of a male model in a classroom where female students were present. Though initially reprimanded by the Academy for violating policy, Eakins and the Academy faced a flurry of accusations, and Eakins was abruptly ousted by the board of directors.

Had his completion of Swimming one year earlier set the wheels in motion for Eakins' enemies to force him out? A commission, Swimming was promptly rejected by Edward H. Coates (1846-1921), chairman of the Academy's Committee on Instruction, who did not deem it appropriate to be included in the school's permanent collection. Alternatively, Coates traded it for The Pathetic Song (1881). Had opposition to Eakins' teaching methods -- or more accurately, toward the artist himself -- been building all along and the "loincloth scandal" was merely the crescendo to a furiously reverberating aria that could only reach its climax with Eakins' removal from the Academy? Swimming had certainly caused a stir, given that all of its subjects -- namely art critic Talcott Williams (reclining on the rocks), students Benjamin Fox (the redheaded young man in the water), John Laurie Wallace (kneeling on the rocks), Jessie Godley (the standing figure), George Reynolds (who is diving into the water), Eakins' setter, Harry, and, of course, Eakins himself -- were easily identifiable. While many consider Swimming to be a masterpiece, a celebration of male beauty, harkening to halcyon days of simpler times when male swimmers typically frolicked in the nude, it goes without saying that in recent years critics have symbolically likened Eakins to a hungry predator stealthily gliding as if undetected through the placid waters of Bryn Mawr's Dove Lake in pursuit of his unsuspecting victims. Whether this metaphor accurately described Eakins and his relationship with students, it can be said that neither Williams nor the young men appear as victims in Swimming or the array of photographs taken as reference material. However, the painting arguably points to inappropriate conduct between a professor and his students.

Stunning Revelations and Accusations

Thomas Eakins' early works included various portraits, rowing scenes, including Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (1871), and the monumental painting, The Gross Clinic (1875), a shockingly realistic portrayal of the famous surgeon, Dr. Samuel D. Gross (1805-1884), at work in the surgical theater. One of the greatest American paintings of the nineteenth century, The Gross Clinic sold for $68 million in 2006.

In 1879, Eakins joined the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, as an assistant to Christian Schuessele (1824-1879), who was failing in health and serving as professor in name only. Eakins basically revamped the curriculum in Schuessele's absence and worked without compensation while Schuessele continued to receive much-needed income from the school. Following Schuessele's death, Eakins was named Professor of Drawing and Painting in August 1879 and became the director of the Academy in 1882. Right away, he disregarded some long-standing rules, including those prohibiting the use of students as nude models. In an era in which women wore full-skirted dresses, it must have seemed outrageous that a male model might be asked to pose in women's life classes. Nonetheless, Eakins tredged on, having students pose for his own works, posing both male and female students for his Naked Series of photographs and even exposing himself to a female student under the auspices of showing pelvic movment. Eakins, no doubt, crossed any number of lines, but his openness to working with nudes proved trendsetting. In a piece for Antiques & Fine Art Magazine, Dr. Cynthia Roznoy wrote, "Eakins' efforts shifted the whole of art teaching in America; by the turn-of-the-century life classes were sanctioned and the male nude emerged from his classical guise to be seen as a contemporary subject" (2012, 152-157).

At the age of forty, Eakins married twenty-five-year-old Susan Hannah Macdowell (1851-1938), and their marriage would conspicuously remain a childless one. The two had met at the Hazeltine Gallery in 1876 during an exhibition of The Gross Clinic. Macdowell had been intrigued by the controversial painting and went on to study with Eakins at the Academy where she became a proponent of including women in life-drawing classes in which the models were nude. In 1886, Eakins was forced to resign from the Academy after he removed the loincloth of a male model in a classroom where female students were present. Though initially reprimanded by the Academy for violating policy, Eakins and the Academy faced a flurry of accusations, and Eakins was abruptly ousted by the board of directors.

Had his completion of Swimming one year earlier set the wheels in motion for Eakins' enemies to force him out? A commission, Swimming was promptly rejected by Edward H. Coates (1846-1921), chairman of the Academy's Committee on Instruction, who did not deem it appropriate to be included in the school's permanent collection. Alternatively, Coates traded it for The Pathetic Song (1881). Had opposition to Eakins' teaching methods -- or more accurately, toward the artist himself -- been building all along and the "loincloth scandal" was merely the crescendo to a furiously reverberating aria that could only reach its climax with Eakins' removal from the Academy? Swimming had certainly caused a stir, given that all of its subjects -- namely art critic Talcott Williams (reclining on the rocks), students Benjamin Fox (the redheaded young man in the water), John Laurie Wallace (kneeling on the rocks), Jessie Godley (the standing figure), George Reynolds (who is diving into the water), Eakins' setter, Harry, and, of course, Eakins himself -- were easily identifiable. While many consider Swimming to be a masterpiece, a celebration of male beauty, harkening to halcyon days of simpler times when male swimmers typically frolicked in the nude, it goes without saying that in recent years critics have symbolically likened Eakins to a hungry predator stealthily gliding as if undetected through the placid waters of Bryn Mawr's Dove Lake in pursuit of his unsuspecting victims. Whether this metaphor accurately described Eakins and his relationship with students, it can be said that neither Williams nor the young men appear as victims in Swimming or the array of photographs taken as reference material. However, the painting arguably points to inappropriate conduct between a professor and his students.

Well before a heightened awareness of sexual harassment became commonplace in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, some had asked why a man of authority and influence was permitted to audaciously cavort with students. As the students knowingly or unwittingly joined Eakins in railing against social and professional parameters in the classroom and at extracurricular locales, were they doing so out of a mutual appreciation (sexual or nonsexual) for the human form, or out of complete innocence or ignorance, or perhaps due to obedience and loyalty to their beloved instructor? Author Alice A. Carter writes, "Eakins, who had no compunction about removing his clothes, made it his mission to strip his students of any shame they might feel about baring all" (2001, 74). As liberating as this sounds, one must remember the conservative era in which Eakins and his students, and their parents, lived. Regardless, Eakins was the professor, and the easily recognized young chaps in his nude paintings and photographs and the act of badgering female students to pose nude, as well as his employment of vulgar euphemisms for body parts and adolescent-like references to bodily functions, all served to kindle the flames of an effort that had been underway to squarely kick him out of the Academy.

Charles Bregler (1864-1958), who would become a portraitist and sculptor, was among a group of students who left the Academy and studied with Eakins at the newly formed Art Students' League in response to Eakins' Academy departure. Bregler was enrolled throughout the duration of the League's seven-year existence. A lifelong friend to Eakins and his widow, Susan Macdowell Eakins, Bregler was the recipient of a massive collection of Eakins' minor works, papers and memorabilia following the death of the artist. Bregler would eventually sell or donate some of Eakins' works to important museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Closely guarded by Bregler's widow upon his death, the remaining items in the collection were allowed to be viewed only by the Academy's curator Kathleen A. Foster and art history authority Elizabeth A. Milroy in the early 1980s, which led to the outright acqusition of the Bregler Collection in 1985 by the Academy. Decades after Eakins' death, the papers would shed much light on Eakins and the Academy's decision to remove him.

The Verdict

Throughout his career and posthumously, Eakins has had his share of vigorous defenders and unforgiving critics. Perhaps most notable among his supporters, of course, were the art school students who left the Academy in protest following his ouster. It bears pointing out that all fifty-five of his male students and eighteen of the thirty female students signed a petition, threatening to leave the Academy unless Eakins' teaching role was restored. It is to be surmised that the sixteen who started the Art Students' League would not have urged him to come on board if they had felt exploited or sexually victimized. Further, some of these students developed into accomplished artists and are said to have remained lifelong friends with Eakins. Providing a glowing defense of the artist in his Eakins biography, Roland McKinney, director of the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art at the time of his book's publication, stated that when Eakins came to the Academy "it was no longer anathema to work from the nude model but soon the tide of 'morality' rose again more vehemently than ever" (1942, 19). McKinnie insists that Eakins' "admiration of the nude was genuinely wholesome, born of the goodness and love of beauty that was in him" (1942, 16).

Others have not been so generous in their summations.

Mary Panzer, former curator of photography at Washington's National Portrait Gallery, has asked whether Eakins was homosexual or simply a troublemaker seeking to elicit shock or anger among those who viewed his work. "To some artists, such a reaction is like oxygen," she wrote in the Chicago Tribune, before stating the obvious: "But after a while, you start to wonder whether Eakins' perverse spirit was just camouflage for a more serious, subversive obsession. With sex. Or men" (2002). Such conjecture is reinforced by Eakins' friendship with poet and Leaves of Grass author Walt Whitman (1819-1892), who is widely believed to have been homosexual. William Duckett -- dogged by a troubled past, perhaps viewed as a charity case and presumed by some to have been Whitman's boy lover -- is the subject of various photographic nudes by Eakins, and it is interesting that several of Eakins' male students referred to themselves as "us Whitman fellows," an apparent nod to a commonality shared between the famous poet and themselves.

If embracing an alternative sexuality in the late 1800s, or employing nude models in his art classes, was his worst offense, Eakins might even be celebrated as a daring visionary, well ahead of his times, in some circles in today's climate. However, in recent years he has been the subject of renewed scrutiny. Most scathing of twenty-first century explorations of Eakins' life and career is the work of Henry Adams, who delves into the canon of Eakins scholarship, pointing to the contradictory responses to allegations that Eakins engaged in everything from sexual harassment and child molestation to bestiality and incest. Enduring more than a century later is belief -- by some, at least -- in the rumor that Eakins, his wife, Susan, and Addie Williams engaged in a ménage à trois. Such accusations, many of them leveled at Eakins by his inlaws and other close relations, have been acknowledged by some biographers, but have often been brushed aside in light of the narrative perpetuated in early Eakins biographies such as Lloyd Goodrich's book, Thomas Eakins: His Life and Work (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1933). Adams further states in Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist that the Bregler papers "suggest that our view of Eakins's personality needs to be completely revised, and that our understanding of the deeper motives of his art has been heavily sugarcoated" (2005, 44). While some have interpreted the revelations of the Bregler papers (which include telling letters) as confirmation that Eakins' forced departure from the Academy was the result of an overthrow by his colleagues, Adams explains: "What the papers reveal instead is that the complaints against Eakins were bitter and personal, rather than professional, and that many of those who were closest to him, including members of his immediate family, had grave doubts about his moral character" (2005, 50).

To say that Eakins' work speaks for itself and reveals his motives, for example, in using nude models in "mixed company" to educate students about the human form, is to suggest that his boldness as an educator, or his great portfolio of work, rules out the possibility that improprieties, even minor ones, could have occurred. However, great artists, thinkers and innovators are not immune from behaving badly. At the same token, it might be reckless to imply that nudity always has sexual or sexually immoral connotations. Some observers could plausibly inquire why those questioning Eakins' sexual tendencies seem intent on fixating on the display of men's buttocks in The Gross Clinic (1875), Swimming (1885) or Salutat (1898). Was Eakins not merely painting what he saw or realistically envisioned? Might such fixations reveal as much about the critics as they do Eakins' supposed preoccupations? Furthermore, if physicians can examine unclad patients, athletes can shower together and naturists -- in some locales such as Munich's Englischer Garten park -- can publicly lounge en masse without resorting to vice, surely an artist can paint willing, undressed models of either sex without having to account for his or her motives. Further, one would think that a male artist should be able to work with male nudes without the resulting work instantly earning the label "homoerotic," which is used so prevalently in some art collecting circles. That said, views on body image, nudity displays, morality and sexuality, especially homosexuality, are far more relaxed in America in the twenty-first century than they were in Quaker Philadelphia when the revolutionary Eakins stretched the boundaries and challenged prudent conventions of the 1880s. Still, there are all those allegations against Eakins. Very serious ones. Alice Carter writes, "It is difficult to know whether Eakins's indiscretions were the premeditated transgressions of a sex offender or if he made mistakes of judgment as a result of an obsessive commitment to the study of the human body" (2001, 75-76).

So, what exactly is the naked truth about Thomas Eakins? His passion for the human physique is evident. His technique with a brush and his master of realism are exemplary. As for Eakins' true intentions regarding controversial events that transpired, surely art aficionados and historians, and perhaps even sociologists, will continue the debate, with some claiming that he was a persecuted, far-sighted creative and others countering that he was a repulsive sexual deviant, most worthy of prosecution, and certainly undeserving of the century's worth of praise that has been lauded upon the artist's work via school textbooks, journal articles, books of academic interest and museum exhibitions. As is often the case between two divergent narratives regarding the same person or subject, the truth might likely be found somewhere in between.

Adams, Henry, Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist, New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Carter, Alice A., The Essential Thomas Eakins, New York: The Wonderland Press, 2001.

Homer, William Innes, Thomas Eakins: His Life and Art, New York: Abbeville Press, 1992.

McKinney, Roland, Thomas Eakins, New York: Crown Publishers, 1942.

Panzer, Mary, "Was Eakins gay--or just a real troublemaker?" Chicago Tribune, 31 July 2002.

Roznoy, Cynthia, "Male Beauty in Milton Bellin's Physical Education," Antiques & Fine Art Magazine, Autumn/Winter, 2012.

Charles Bregler (1864-1958), who would become a portraitist and sculptor, was among a group of students who left the Academy and studied with Eakins at the newly formed Art Students' League in response to Eakins' Academy departure. Bregler was enrolled throughout the duration of the League's seven-year existence. A lifelong friend to Eakins and his widow, Susan Macdowell Eakins, Bregler was the recipient of a massive collection of Eakins' minor works, papers and memorabilia following the death of the artist. Bregler would eventually sell or donate some of Eakins' works to important museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Closely guarded by Bregler's widow upon his death, the remaining items in the collection were allowed to be viewed only by the Academy's curator Kathleen A. Foster and art history authority Elizabeth A. Milroy in the early 1980s, which led to the outright acqusition of the Bregler Collection in 1985 by the Academy. Decades after Eakins' death, the papers would shed much light on Eakins and the Academy's decision to remove him.

The Verdict

Throughout his career and posthumously, Eakins has had his share of vigorous defenders and unforgiving critics. Perhaps most notable among his supporters, of course, were the art school students who left the Academy in protest following his ouster. It bears pointing out that all fifty-five of his male students and eighteen of the thirty female students signed a petition, threatening to leave the Academy unless Eakins' teaching role was restored. It is to be surmised that the sixteen who started the Art Students' League would not have urged him to come on board if they had felt exploited or sexually victimized. Further, some of these students developed into accomplished artists and are said to have remained lifelong friends with Eakins. Providing a glowing defense of the artist in his Eakins biography, Roland McKinney, director of the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art at the time of his book's publication, stated that when Eakins came to the Academy "it was no longer anathema to work from the nude model but soon the tide of 'morality' rose again more vehemently than ever" (1942, 19). McKinnie insists that Eakins' "admiration of the nude was genuinely wholesome, born of the goodness and love of beauty that was in him" (1942, 16).

Others have not been so generous in their summations.

Mary Panzer, former curator of photography at Washington's National Portrait Gallery, has asked whether Eakins was homosexual or simply a troublemaker seeking to elicit shock or anger among those who viewed his work. "To some artists, such a reaction is like oxygen," she wrote in the Chicago Tribune, before stating the obvious: "But after a while, you start to wonder whether Eakins' perverse spirit was just camouflage for a more serious, subversive obsession. With sex. Or men" (2002). Such conjecture is reinforced by Eakins' friendship with poet and Leaves of Grass author Walt Whitman (1819-1892), who is widely believed to have been homosexual. William Duckett -- dogged by a troubled past, perhaps viewed as a charity case and presumed by some to have been Whitman's boy lover -- is the subject of various photographic nudes by Eakins, and it is interesting that several of Eakins' male students referred to themselves as "us Whitman fellows," an apparent nod to a commonality shared between the famous poet and themselves.

If embracing an alternative sexuality in the late 1800s, or employing nude models in his art classes, was his worst offense, Eakins might even be celebrated as a daring visionary, well ahead of his times, in some circles in today's climate. However, in recent years he has been the subject of renewed scrutiny. Most scathing of twenty-first century explorations of Eakins' life and career is the work of Henry Adams, who delves into the canon of Eakins scholarship, pointing to the contradictory responses to allegations that Eakins engaged in everything from sexual harassment and child molestation to bestiality and incest. Enduring more than a century later is belief -- by some, at least -- in the rumor that Eakins, his wife, Susan, and Addie Williams engaged in a ménage à trois. Such accusations, many of them leveled at Eakins by his inlaws and other close relations, have been acknowledged by some biographers, but have often been brushed aside in light of the narrative perpetuated in early Eakins biographies such as Lloyd Goodrich's book, Thomas Eakins: His Life and Work (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1933). Adams further states in Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist that the Bregler papers "suggest that our view of Eakins's personality needs to be completely revised, and that our understanding of the deeper motives of his art has been heavily sugarcoated" (2005, 44). While some have interpreted the revelations of the Bregler papers (which include telling letters) as confirmation that Eakins' forced departure from the Academy was the result of an overthrow by his colleagues, Adams explains: "What the papers reveal instead is that the complaints against Eakins were bitter and personal, rather than professional, and that many of those who were closest to him, including members of his immediate family, had grave doubts about his moral character" (2005, 50).

To say that Eakins' work speaks for itself and reveals his motives, for example, in using nude models in "mixed company" to educate students about the human form, is to suggest that his boldness as an educator, or his great portfolio of work, rules out the possibility that improprieties, even minor ones, could have occurred. However, great artists, thinkers and innovators are not immune from behaving badly. At the same token, it might be reckless to imply that nudity always has sexual or sexually immoral connotations. Some observers could plausibly inquire why those questioning Eakins' sexual tendencies seem intent on fixating on the display of men's buttocks in The Gross Clinic (1875), Swimming (1885) or Salutat (1898). Was Eakins not merely painting what he saw or realistically envisioned? Might such fixations reveal as much about the critics as they do Eakins' supposed preoccupations? Furthermore, if physicians can examine unclad patients, athletes can shower together and naturists -- in some locales such as Munich's Englischer Garten park -- can publicly lounge en masse without resorting to vice, surely an artist can paint willing, undressed models of either sex without having to account for his or her motives. Further, one would think that a male artist should be able to work with male nudes without the resulting work instantly earning the label "homoerotic," which is used so prevalently in some art collecting circles. That said, views on body image, nudity displays, morality and sexuality, especially homosexuality, are far more relaxed in America in the twenty-first century than they were in Quaker Philadelphia when the revolutionary Eakins stretched the boundaries and challenged prudent conventions of the 1880s. Still, there are all those allegations against Eakins. Very serious ones. Alice Carter writes, "It is difficult to know whether Eakins's indiscretions were the premeditated transgressions of a sex offender or if he made mistakes of judgment as a result of an obsessive commitment to the study of the human body" (2001, 75-76).

So, what exactly is the naked truth about Thomas Eakins? His passion for the human physique is evident. His technique with a brush and his master of realism are exemplary. As for Eakins' true intentions regarding controversial events that transpired, surely art aficionados and historians, and perhaps even sociologists, will continue the debate, with some claiming that he was a persecuted, far-sighted creative and others countering that he was a repulsive sexual deviant, most worthy of prosecution, and certainly undeserving of the century's worth of praise that has been lauded upon the artist's work via school textbooks, journal articles, books of academic interest and museum exhibitions. As is often the case between two divergent narratives regarding the same person or subject, the truth might likely be found somewhere in between.

Adams, Henry, Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist, New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Carter, Alice A., The Essential Thomas Eakins, New York: The Wonderland Press, 2001.

Homer, William Innes, Thomas Eakins: His Life and Art, New York: Abbeville Press, 1992.

McKinney, Roland, Thomas Eakins, New York: Crown Publishers, 1942.

Panzer, Mary, "Was Eakins gay--or just a real troublemaker?" Chicago Tribune, 31 July 2002.

Roznoy, Cynthia, "Male Beauty in Milton Bellin's Physical Education," Antiques & Fine Art Magazine, Autumn/Winter, 2012.

Copyright 2020-2024 PhillyDally.com

All Rights Reserved.

All Rights Reserved.

PhillyDally.com, part of the Greg Freeman Media portfolio of digital resources, can be contacted via e-mail: philly dally at outlook dot com.